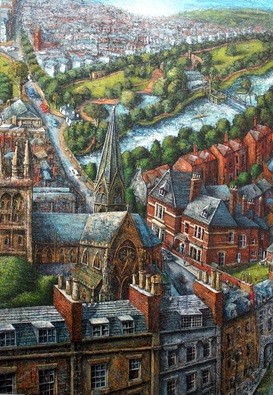

I've just been admiring this amazing new painting of our neighbourhood by Adrian Sykes. The painting was a commission, and Adrian came to All Saints' a few months ago to climb the bell-tower and take some of the photos he used to construct it. I was glad of the invitation to view the finished item, and very interested to see it.

One of the fascinating things about it is the incorporation of certain easily recognisable features of the town - including the church - whilst subtly changing the perspective and locations. The result is a work which is really rather entrancing; a fresh way of perceiving familiar places and landmarks, and relating them to one another.

In the book English Passengers by Matthew Kneale, the Aboriginal character Peevay records his childhood rootedness in the ancestral landscape of Tasmania. Peevay was familiar with the routes and landmarks of the tribal area; but more significantly, he learned to interpret them in accordance with the traditional shared understanding of his people. His sense of belonging, meaning and identity developed as he grew up nourished by the legends and beliefs of his tribe:

“Little by little I began to recollect places where we went, till I knew those hills and mountains and even where the world stopped. Slowly slowly I could solve some of those puzzles to confound. Tartoyen…told us stories - secret stories that I will not say even now…Also he told us who was in those rocks and mountains and stars, and how they went there. Until, by and by, I could hear stories as we walked across the world, and divine how it got so, till I knew world as if he was some family fellow of mine.”

Our world-view may differ considerably, but we still construct our sense of belonging through particular places - not only those of general interest, such as the church, but also others which may have little if any meaning to the public at large but which matter to us. Our own home, of course; a gateway here, a tree there, a place on the riverbank or in the park, somewhere we go to school or to work. The meanings accrue through memories, through specific experiences and through growing familiarity; and just as in the painting above, we construct our own individual perspective on the world - our own 'secret stories' by which we interpret our neighbourhood.

Something similar happens as we grow in Christian faith. We share the key truths, the general features which, like the church, the River Leam, the Parade, the Jephson Gardens in the painting, may vary in their prominence and precise relation to one another. We develop a familiarity with other landmarks - particular Bible stories, characters, or verses, for example - maybe because they resonate with our circumstances, or perhaps because of a memorable sermon, painting or stained-glass window. Favourite hymns, the lives and examples of faithful, loving people, and our own spiritual experiences flesh out the details. We learn to fill in the shadows too, when we encounter more difficult times such as illness, bereavement or conflict. Little by little, we construct a picture, an overarching story or meta-narrative, a world-view which gives meaning to our life and enables us to hold our faith together.

Yes, our perspectives may differ; some of the details may be hazy or inaccurate; perhaps we're missing some of the features which others would consider essential and including what others would overlook. But as we journey through the Christian year and through the challenges and triumphs of our lives, we find our sense of belonging, meaning and identity increasingly in the faith we seek to live out.

And so to an abstract question. What would it look like if you were to paint, not your personal landscape of the town, but your construction of the faith? What would be the most prominent aspects, what else would be included, and how would it all hold together? What might be missing which others would see as essential? And what might God call you to change: in terms of prominence and priority; in terms of what is there and what isn't; in terms of the details which are lacking and the perspectives which need correction?

One of the fascinating things about it is the incorporation of certain easily recognisable features of the town - including the church - whilst subtly changing the perspective and locations. The result is a work which is really rather entrancing; a fresh way of perceiving familiar places and landmarks, and relating them to one another.

In the book English Passengers by Matthew Kneale, the Aboriginal character Peevay records his childhood rootedness in the ancestral landscape of Tasmania. Peevay was familiar with the routes and landmarks of the tribal area; but more significantly, he learned to interpret them in accordance with the traditional shared understanding of his people. His sense of belonging, meaning and identity developed as he grew up nourished by the legends and beliefs of his tribe:

“Little by little I began to recollect places where we went, till I knew those hills and mountains and even where the world stopped. Slowly slowly I could solve some of those puzzles to confound. Tartoyen…told us stories - secret stories that I will not say even now…Also he told us who was in those rocks and mountains and stars, and how they went there. Until, by and by, I could hear stories as we walked across the world, and divine how it got so, till I knew world as if he was some family fellow of mine.”

Our world-view may differ considerably, but we still construct our sense of belonging through particular places - not only those of general interest, such as the church, but also others which may have little if any meaning to the public at large but which matter to us. Our own home, of course; a gateway here, a tree there, a place on the riverbank or in the park, somewhere we go to school or to work. The meanings accrue through memories, through specific experiences and through growing familiarity; and just as in the painting above, we construct our own individual perspective on the world - our own 'secret stories' by which we interpret our neighbourhood.

Something similar happens as we grow in Christian faith. We share the key truths, the general features which, like the church, the River Leam, the Parade, the Jephson Gardens in the painting, may vary in their prominence and precise relation to one another. We develop a familiarity with other landmarks - particular Bible stories, characters, or verses, for example - maybe because they resonate with our circumstances, or perhaps because of a memorable sermon, painting or stained-glass window. Favourite hymns, the lives and examples of faithful, loving people, and our own spiritual experiences flesh out the details. We learn to fill in the shadows too, when we encounter more difficult times such as illness, bereavement or conflict. Little by little, we construct a picture, an overarching story or meta-narrative, a world-view which gives meaning to our life and enables us to hold our faith together.

Yes, our perspectives may differ; some of the details may be hazy or inaccurate; perhaps we're missing some of the features which others would consider essential and including what others would overlook. But as we journey through the Christian year and through the challenges and triumphs of our lives, we find our sense of belonging, meaning and identity increasingly in the faith we seek to live out.

And so to an abstract question. What would it look like if you were to paint, not your personal landscape of the town, but your construction of the faith? What would be the most prominent aspects, what else would be included, and how would it all hold together? What might be missing which others would see as essential? And what might God call you to change: in terms of prominence and priority; in terms of what is there and what isn't; in terms of the details which are lacking and the perspectives which need correction?

RSS Feed

RSS Feed